As discussed previously, the purpose of the second blog post is to explore the specific components of a warm-up routine and piece everything together for practical application. If you’re wondering WHY warming up is important.

Components of a warm-up routine

- General warm-up*

- Mobility/Dynamic Stretching

- Muscle Activation

- Barbell Warm-Up*

*Essential components of a warm up

Note: For simplification, this article will assume that gym-goers proceed to barbell movements after warm-ups. Barbell warm-ups can also be substituted to movements specific to their training plan that day (ie. Kettlebell, Trap-bar, machine chest press, etc).

Do take note that you do not have to go through all 4 components religiously. If you currently do not have a habit of warming up, I would highly recommend that you incorporate the asterisked points first. In order for healthy sustainable habits to form, it must be easy for you to implement and repeat regardless of your environment. Remember, making small changes is enough to increase your self-efficacy. Aim towards making your warm-up routine an automatic and effortless one.

If you’re someone who has the habit of warming up routinely prior to every session, I challenge you to think about your current routine and how you can maximise the specificity and efficiency of your routine. You do not have to build a new routine, but you have to insist on getting the most bang for your buck in the movements that you have chosen. A good way to tell if your routine is working is by taking note of any variations to your performance level (e.g., Do your joints feel less stiff? Are you able to feel your muscles better?). Similarly, if you make adjustments to your routine, compare your performance level before and after these adjustments. This subjective indicator should tell you if what you’re doing is working.

Component 1: General Warm-up

The goal of a general warm-up is to increase your body temperature and heart rate. Increased muscle temperature improves muscle elasticity and contractile function, allowing for more efficient force production during lifting movements.

While most lifters nauseate at the thought of doing cardio, Cesar et al. (2011) found that athletes who included a general cardiovascular warm-up prior to performing a leg-press 1-rep-max Test increased their strength by 8.4% on average compared with those who just started warming up with weights.

Practical Application

Duration: 5 minutes

Modalities to consider: Brisk walking, light jogging, Biking, Rowing, Skipping, SkiErg, Sled pulls/push, Elliptical trainer, Stairmaster

Intensity: Low – Moderate (You should be breaking a light sweat, and can hold a short conversation)

Note: If you’re training in an outdoor/hot environment, make sure you’re well-hydrated and be careful not to overshoot the intensity during warm-ups to prevent fatigue from affecting your actual working sets.

Component 2: Mobility & Dynamic Stretching

These days, mobility work & dynamic stretching seem as popular as actually improving strength and athleticism. Far too many people overemphasize this portion of their warm-up thinking that it is the answer to their poor movement patterns. However, many fail to understand the purpose of mobility work and dynamic stretching.

Defining dynamic stretching

Dynamic stretching is a movement-based type of stretching. It requires active movements where joints and muscles themselves go through a full range of motion to bring about a stretch. This again increases body temperature and increases blood flow to the targeted muscle groups. It differs from static stretching because the stretch position is not held.

Defining mobility

Mobility includes soft tissue flexibility/extensibility as well as joint range of motion, arthrokinematics (small accessory movement within a joint), and osteokinematics (larger movements of bones at joints in the three planes) (Henoch, 2015). The purpose of performing mobility work is to improve your potential to produce a desired movement pattern (e.g., mobilizing your ankles to improve squat depth) and it is usually achieved by improving blood flow to the muscles and increasing your range of motion.

The funny thing is, increasing blood flow to your muscles and increasing your range of motion isn’t hard to achieve. If you rub any part of your skin hard and fast enough, there would be an increase in blood flow to that region. Another commonly held belief is the idea that self-myofascial techniques (e.g., foam rollers) help to break up adhesions, and scar tissues, and restore sliding surfaces. The current stand in literature is that it is beyond our physiological ability to create the necessary shear force in our tissues to cause an abrupt structural change (Wilke et al., 2020).

Practical Application

- Mobility work & dynamic stretching are both corrective in nature, which means that they should be preceded by some form of technique analysis or movement assessment.

- Changes after mobility work and dynamic stretching should occur quickly. Foam rolling for 3 mins isn’t 6x better than foam rolling for 30 seconds. Your nervous system is highly adaptable, it learns and responds quickly. You need to figure out the minimum dosage for you to feel the release or improvement in range, and then proceed to reassess the quality of your movement (e.g. squat depth limited by tight calves → foam roll the calves → checking if squat depth has improved). Generally, you should not take more than 5 mins and 1 set of 8-10 reps/exercise is enough.

- Besides soft tissues like muscles, you can also perform banded mobilisations to assist with joint restrictions. You can think of joint restrictions as a loss of space between bones. A common result of joint restriction is impingement, which is usually felt as a ‘pinching’ or ‘blocked’ sensation.

- If you’re still insisting that foam rolling is the answer to life, be sure that it is done to target the muscle groups that are specific to your movement.

For squats: spinal erector (lower back), quads, hamstrings, glutes, or calves.

For bench press: lats, pecs, triceps, or spinal erectors.

For deadlift: lats, quads, hamstrings, spinal erectors, or inner thighs

The reason why mobility and dynamic stretching are not essential in a warm-up routine is that it is highly individualized. As long as your body is able to repeatedly perform the ideal movement patterns, your tissues will adapt accordingly, and the need for correctives should diminish.

Note: If your priority is learning how to get into the ideal position for a lift (e.g. increasing stance wide for sumo deadlift or improving thoracic extension for the bench), then mobility would be essential.

Component 3: Muscle Activation

This component is a great tool to use if you tend to not feel your muscles when performing certain lifts (e.g., glutes when deadlifting). Muscle activation movements can help increase your overall neuromuscular efficiency (Parr, Price & Cleather, 2017). These activation exercises are basic motions that are centered around learning to isolate and engage a particular muscle. They should be easy and targeted at a singular muscle so that you can clearly feel its activation. In general, they allow for less compensation (e.g., it’s easier to feel your glutes when performing a single-leg glute bridge rather than when squatting) because fewer muscles are working at the same time.

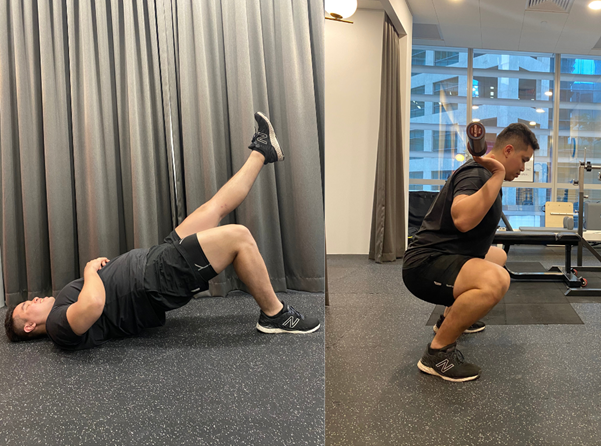

Left: Single Leg Glute Bridge, Right: Barbell Squat

Here’s an example: you might have experienced trouble with staying upright at the bottom during a squat. As you get out of the hole, your squat becomes more of a good morning, with your hips shooting up and your chest collapsing. Your knees simultaneously proceed to cave in but you somehow manage to finish the rep. This may be due to several reasons, but one possible explanation is that your glutes, the muscle that is responsible for external hip rotation (helps with driving your knee outwards), aren’t recruited effectively or strong enough while you were driving out of the hole. Therefore, it may be ideal to add in some glute activation exercises (e.g., forefoot banded crab walks) as part of your warm-up to ensure that it is primed and ready to support the forces at the level of the hip joint during squatting.

If the example above is relatable, it may be worth it to try it out. But again, it is not the definitive solution to your issue. The reason why this is not an asterisked component is that appropriate muscle activation drills differ greatly from the individual. How you feel during a squat vs. how others feel is completely different. Some lifters may just have better muscle recruitment patterns because of their training history and anthropometric differences.

Practical Application

Here are some takeaways when performing muscle activation (Pollack, 2019):

- You need to figure out which muscles you need to focus on, and find the right exercises to help you activate those muscles. A good question to ask yourself is: Am I feeling the right muscles?

- 1-2 exercise(s) of 8-10 reps/movement is enough. The goal is to engage your muscles, not fatigue them. As such, we want to keep the resistance fairly light and use a controlled tempo to ensure you’re not compensating with bigger muscle groups. Focus on the ‘mind-muscle connection’.

- Do not be afraid to get creative with isolation exercises. Some unconventional exercises seem to work better than more common ones, the end result is what matters. You can even explore using machines because they place your body in a position where the target muscle will work.

- Over time, do not forget to rotate the activation exercises to add variation. It’s always important to reevaluate how to maximise the benefits of your activation drills.

Component 4: Barbell Warm-up

Now that you’re warm, mobile, and activated, you are ready to warm up with a barbell. Never jump straight into your working weights, even on a light day: even if your body is capable of getting straight to it because there’s a lot of value in easing into your main lifts. Gymgoers tend not to plan the exact intensity and reps leading up to their top set because they tend to load according to their convenience.

The purpose is to utilise a light barbell warm-up to stimulate the neuromuscular and proprioceptive responses to the compound lifts through simulated movement patterns, which allow you to practice, reinforce and improve your technique (Racinais, Cocking & Périard, 2017). It also gives you the time to adjust to the feeling of heavier weights and allows you to identify any possible issues like tight muscles or joint discomfort. In such cases, you can do additional warm-ups or lighten your planned loads to optimise your session. In and of itself, this is the most essential component of warming up for most gym-goers. The barbell warm-up also gets you the most benefits during your warm-up because of its specificity.

Practical Application

Below provides an example of how you can approach your barbell warm-up:

| Warm Up for working set | |

| Set #1 | Empty Bar x 6 – 10 Reps |

| Set #2 | 30 – 40% of working set x 6 Reps |

| Set #3 | 50 – 60% of working set x 3 – 5 Reps |

| Set #4 | 70 – 80% of working set x 3 – 5 Reps |

| Set #5 | 80 – 85% of working set x 1 – 3 Reps |

Do note that the rep ranges and intensity can be altered depending on how you’re feeling. On bad training days, don’t be afraid to retake warm-up sets. It is always better to be cautious so that you’re prepared and confident for the sets that really count than to rush and underperform. Practice the technique that you want to execute under heavy weight, and begin to focus your attention on the workout at hand.

Conclusion

The components of a general warm-up include:

- General warm-up

- Mobility/Dynamic Stretching

- Muscle Activation

- Barbell Warm-Up

Each of these components should only take you a few minutes, with the entire warm-up taking no longer than 15 minutes. Warm-ups routines should always be dynamic and it will vary from person to person. With enough practice and experimentation over time, you will be able to develop your own unique process.

Always remember to consult your coach/physio and obtain relevant inputs if needed!

References

Abad, C. C., Prado, M. L., Ugrinowitsch, C., Tricoli, V., & Barroso, R. (2011). Combination of general and specific warm-ups improves leg-press one repetition maximum compared with specific warm-up in trained individuals. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(8), 2242-2245. doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181e8611b

Fradkin, A., Gabbe, B., & Cameron, P. (2006). Does warming up prevent injury in sport? Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 9(3), 214-220. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.03.026

Fradkin, A. J., Zazryn, T. R., & Smoliga, J. M. (2010). Effects of warming-up on physical performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(1), 140-148. doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181c643a0

Gardner, B., Lally, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). Making health habitual: The psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 62(605), 664-666. doi:10.3399/bjgp12x659466

Henoch, Q. (2015). 5 mobility rules of thumb, Part 1. Retrieved from https://www.jtsstrength.com/5-mobility-rules-thumb-part-1/

Manoel, M. E., Harris-Love, M. O., Danoff, J. V., & Miller, T. A. (2008). Acute effects of static, dynamic, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on muscle power in women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(5), 1528-1534. doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e31817b0433

McCrary, J. M., Ackermann, B. J., & Halaki, M. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of upper body warm-up on performance and injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(14), 935-942. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094228

McGowan, C. J., Pyne, D. B., Thompson, K. G., & Rattray, B. (2015). Warm-up strategies for sport and exercise: Mechanisms and applications. Sports Medicine, 45(11), 1523-1546. doi:10.1007/s40279-015-0376-x

Parr, M., Price, P. D., & Cleather, D. J. (2017). Effect of a gluteal activation warm-up on explosive exercise performance. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 3(1), e000245. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2017-000245

Pollack, B. (2019). Ben Pollack’s 4 steps to the perfect powerlifting warm-up. Retrieved from https://barbend.com/powerlifting-warm-up/

Racinais, S., Cocking, S., & Périard, J. D. (2017). Sports and environmental temperature: From warming-up to heating-up. Temperature, 4(3), 227-257. doi:10.1080/23328940.2017.1356427

Shellock, F. G., & Prentice, W. E. (1985). Warming-up and stretching for improved physical performance and prevention of sports-related injuries. Sports Medicine, 2(4), 267-278. doi:10.2165/00007256-198502040-00004

Silverberg, A. (2019). How to warm up for Powerlifting (step-by-step guide). Retrieved from https://powerliftingtechnique.com/how-to-warm-up-for-powerlifting/

Wilke, J., Müller, A., Giesche, F., Power, G., Ahmedi, H., & Behm, D. G. (2019). Acute effects of foam rolling on range of motion in healthy adults: A systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 50(2), 387-402. doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01205-7